Readings: Essays & Articles

readings: essays & articles

reassuring ghosts and haunted houses

fish recorded singing dawn chorus on reefs just like birds

what people around the world dream about

poet and philosopher david whyte on anger, forgiveness, and what maturity really means

oranges are orange, salmon are salmon

how memories persist where bodies and even brains do not

the avant-garde musical legacy of the moomins

the weight of our living: on hope, fire escapes, and visible desperation

disturbed minds and disruptive bodies

what is better ー a happy life or a meaningful one?

after my dad died, i started sending him emails. months later, someone wrote me back

on the igbo art of storytelling

what the caves are trying to tell us

promethean beasts — how animal uses of fire help illuminate human pyrocognition

the art of loving and losing female friends

on memorizing poetry

the ecological imagination of hayao miyazaki

reading in the age of constant distraction

holly warburton illustrates tender moments of love and light

romancing the fig: what one fruit can tell us about love, life and human civilization

mystery and birds: 5 ways to practice poetry

can a plant remember? this one seems to — here's the evidence

why female cannibals frighten and fascinate

when you give a tree an email adress

fear not — horror movies build community and emotional resilience

More Posts from Not-this-one and Others

the notes are broken 😂

I have so many feelings about this, but they boil down to the same frustrated rage I've had for a year or more.

I wish Americans fucked with more foreign music. You don’t have to know the language to appreciate a good record. Folks in other countries listen to our music and don’t speak a lick of english. Music needs no translator

Oh my gosh. I just found this website that walks you though creating a believable society. It breaks each facet down into individual questions and makes it so simple! It seems really helpful for worldbuilding!

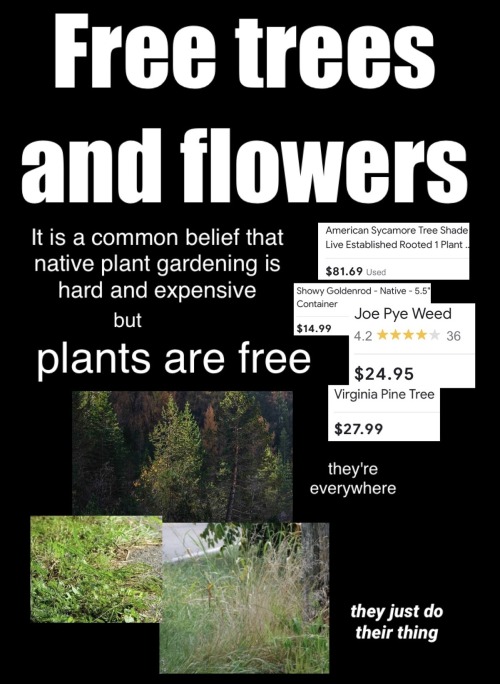

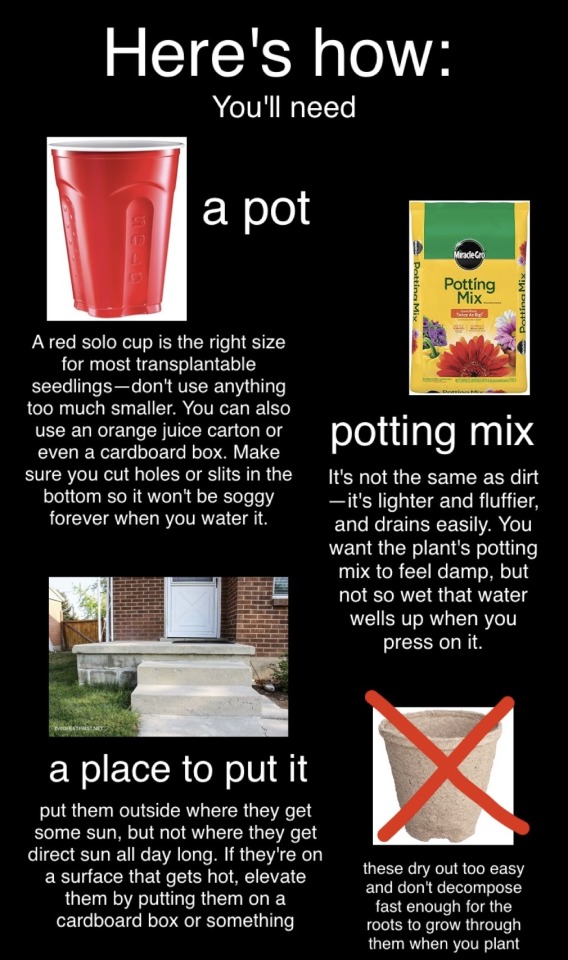

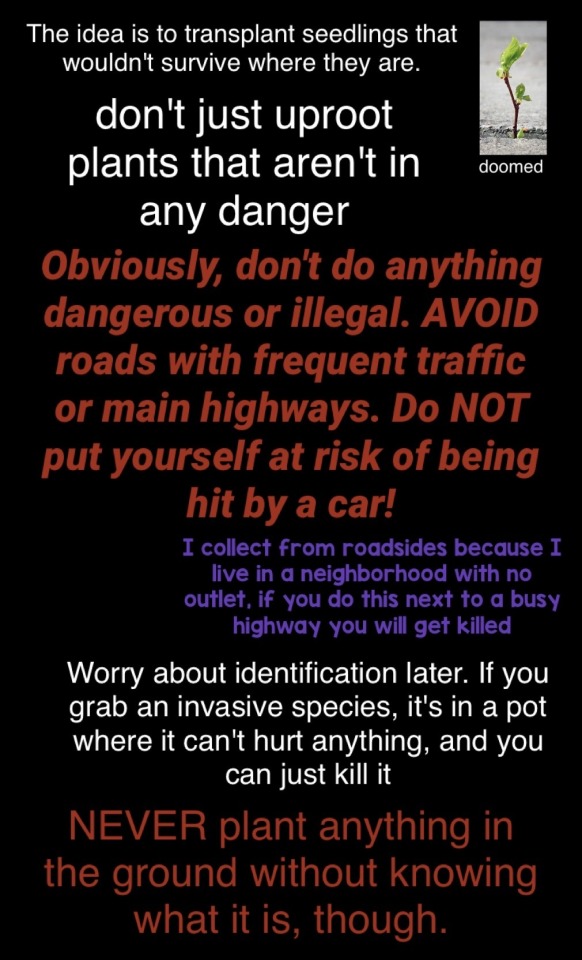

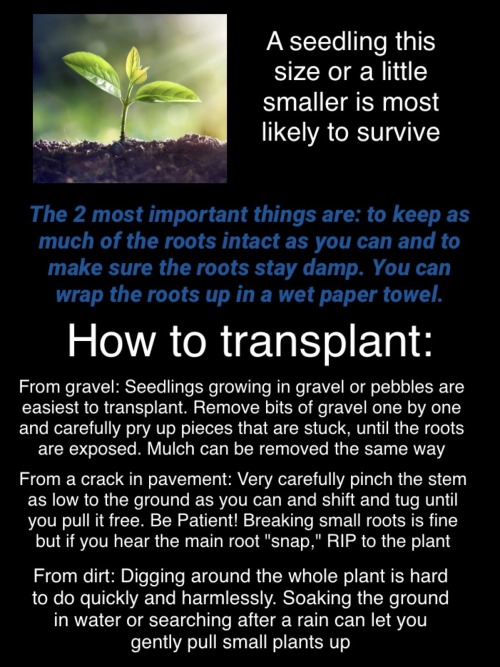

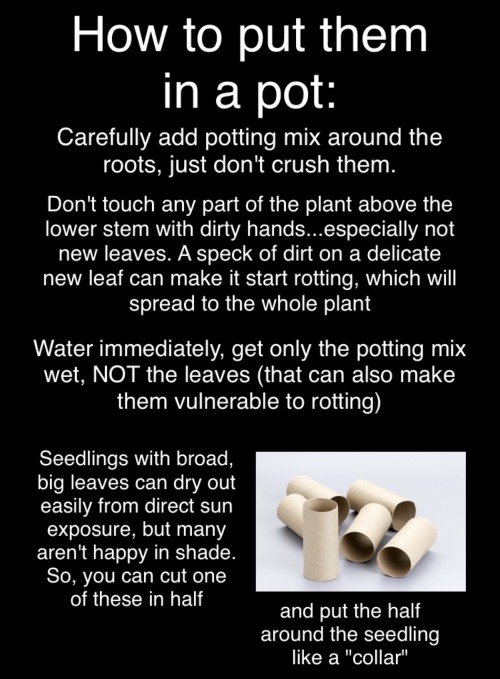

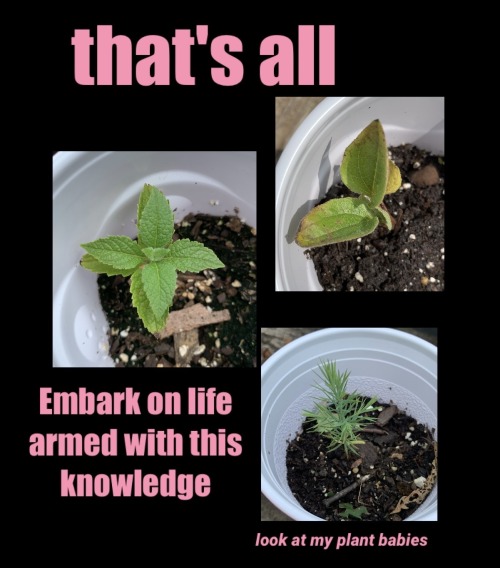

as promised, the transplanting tutorial

most sources make transplanting sound incredibly difficult, but transplanting young seedlings from areas with sparse dirt, like a driveway or roadside, is actually incredibly easy and can get you some great stuff. Once I worked out the method, i've had a very high survival rate

it took me like a month of trial and error to figure this out so you don't have to.

Feel free to repost, no need for credit

i've thought about this a lot and if i had to explain recorded sound to a ghost or a time traveler or an alien i would play them the recording of california song from this tmg show. the quiet simplicity. the person in the audience who shouts "i love you". the way after two lines, john leaves his mic and all you hear is the crowd, but it's small enough that you can pick out individual voices. the person with high voice who hits every note and you can hear their smile. the way the quiet of the first verse turns into a emphatic chant of "i've got joy, joy, joy in my soul tonight". the guy who sings the song the regular way while the rest of the crowd holds a note, and ends up being the only person singing in the audience for a moment. the way the john and the crowd keep singing "you really got a hold on me" until it's just peter's bass and everyone snapping along. the little improvised lines john sings before he says "thank you very much" and the crowd erupts. humanity at its absolute finest for real

YALL

some essays i’ve enjoyed recently:

Anne Boyer - “No”

Parul Sehgal - “The Case Against The Trauma Plot”

Brandon Taylor - “against character vapour”

Jhumpa Lahiri - “Indian Takeout”

S.L. Huang - “The Ghost of Workshops Past”

Frankie Thomas - “What Was it About The Animorphs?”

Carmen Maria Machado - “How Surrealism Enriches Storytelling About Women”

Jaya Saxena - “The Limits of the Lunchbox Moment”

Emma Garland - “What does it mean to be a ‘dissociative feminist?’”

Hussein Omar - “Unexamined Life”

Roland Barthes - “The Death of the Author”

Laura Mulvey - “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Andrea Long Chu - “Hanya’s Boys”

Jia Tolentino - “Love, Death, and Begging For Celebrities to Kill You”

Robin D.G. Kelley - “A Poetics of Anticolonialism”

Angelica Jade Bastien - “The Hollow Impersonation in Blonde”

i’ll probably be adding to this list with more pieces as i come across them– please feel free to add on your own recommendations, or send me an ask if you agree, disagree or want to chat more about any of the essays already listed!

hey pirate show friends! in honor of my boat graduation and because I'm procrastinating my work I thought I'd make a post about some super basic sail mechanics/terminology for all your writing-about-ships needs. this just covers the very broad strokes that you'd need to convincingly talk about what's happening on a ship while there's other stuff going on, or to insert some ship-based drama. I'm not an expert and I'm only practically familiar with one tallship that's much later in period than the Revenge. but here are some things I did not know before sail training that I think could be helpful or provide some fun jumping off points for writing! this is super long but I am super procrastinating. hopefully it's helpful to someone. if not, I at least wasted a fun hour thinking about things that aren't my day job.

1. what are the basic types of sails?

for a square-rigged ship like the Revenge, you will have both "square sails" and "fore-and-aft sails." square sails are set perpendicular to the masts and, obviously, are roughly square. they are "bent onto" (meaning connected to) the "yards," which are the horizontal pieces of wood that cross the mast. fore-and-aft sails are set going, well, fore and aft, meaning they follow the line of the ship. these can include staysails (triangular sails bent onto the "stays," or wires that support the masts, and therefore run down the middle of the ship), jibs (also triangular and bent onto stays or wires, but going out along the jibboom and bowsprit, which are the spars that extend forward of the ship's bow), spankers (a large trapezoidal-ish fore-and-aft sail bent onto booms (basically like a fore-and-aft yard) off the mizzen mast, which is towards the stern of the boat, and acts as a wind rudder), and more. some older ships also had spritsails, which were small square sails bent onto yards that hang off the bowsprit. they look very silly in my opinion but to each their own. these aren't all the kinds of sails but they'll cover your basics.

ships can also have any number of sails. full size square-rigged ships can have as few as two or as many as five square sails on each mast. the lowest and largest sail can be called either the mainsail or the course, and are further specified by saying which mast it's on (i.e., the fore course, main course, or mizzen course). going upwards and assuming a five-sail mast, you've next got the lower topsail, upper topsail, topgallant (pronounced t'gallant), and royal. the staysails are named for the mast they connect to. so the most forward might be the "fore topmast staysail," indicating a sail that is connected to the upper part of the foremast.

2. how are sails controlled?

the vast majority of sail control actually comes from the deck and does not require having people aloft, or in the rigging (I'll address the reasons to have people aloft in the next section).

each sail has a number of "lines" (ropes) connected to it at different points that control whether the sail is "set" (fully extended) or "doused" (pulled up towards the yard). more lines are connected to the yards and control how the sail is oriented. the yards can be pulled back and forth, some of them can be pulled up and down, and their angle relative to the horizon can also be adjusted. the square sails on a mast all work together as they are stacked on top of each other and often have interconnected rigging. the lines all come down to the deck and are "belayed" (a figure-eight shaped way of wrapping the rope) around a "pin." the pins may be on a rail that wraps around the ship (the "pinrail"), on a rail that makes a square shape around a mast (a "fiferail"), or on a metal band wrapped around a mast (a "spider rail.") (there are other rails also, especially on the headdeck, which is the most forward, and the quarterdeck, which is the most aft. don't worry about it.)

some things you might do with sails from deck:

set sails (pulling the foot of the sail all the way to the next lowest yard so that it is fully extended and can fill with wind)

douse sails (pulling the foot of the sail up to its yard so that it is no longer catching as much wind. you can leave the sail doused if you might need to set it again, or you can send people aloft to furl it if you do not need it or are in conditions where it is dangerous to have a loose sail)

conduct manuevers, i.e. turn the ship

the three basic manuevers are tacking, wearing, and boxhauling, but all of them are just ways to turn the ship and change course. you can look up the particulars of these manuevers if you're interested, but I think the most important part from a writing perspective is knowing the initial commands. there are a whole series of commands for each of these manuevers but the opening ones you might most need are:

for a tack, the captain or conn (person in charge of issuing manuevering orders), first calls "ready about!" one of the other orders that might be dramatic to have in a writing situation is "helms a'lee," which occurs after ready about and prompts the person at the helm to turn it.

for a wear (the most common and least work-intensive way to turn most large tallships, though it loses you more ground), the order is "prepare to wear ship!"

for a boxhaul (essentially a three-point turn for when you do not have a lot of space to manuever), the order is "stand by to boxhaul!"

you can also stop the ship by "heaving to" (past tense: "hove to"), where you rotate the yards in opposition to each other so that the sails form a right angle with each other, which loses you all of your wind power.

these might change by period or tradition, but are the most common I'm aware of.

the commands for setting and dousing sails are pretty straightforward- you're just going to say "on the [fore/main/mizzen], set/douse your [sail]!" someone lower in the chain of command might also say "hands to the [sail] gear." whatever needs to get done is then accomplished by hauling on, easing (letting go slowly and under control) or casting off the relevant lines.

4. so what do people do aloft?

going up into the rigging is referred to as "laying aloft." you do this by climbing the "shrouds," which are those things you always see people in Boat Media climbing on-- they look like big nets or ladders that extend from the rails of the ship up to the masts. the shrouds may go to "cranelines" (small footropes that allow you to access the middle of a mast between yards, which is often where staysails are stowed), to platforms/crow's nests, or to "footropes," which are strung under each yard. there is also the "headrig," which is a system of footropes and stays that form what looks like a net under and around the jibboom and bowsprit and allow those areas to be accessed. all of these need to be tarred and otherwise repaired, and if a line parts (breaks) a new one needs to be rigged. masts may also need to be tarred or painted and other hardware might need to be repaired, checked, or replaced, such as "blocks" (pulleys that help lines move), shackles, and hooks. you might also need to bend on sails, or even replace entire masts if you're doing heavy repairs in port. people doing these jobs might carry tools or materials tied off in canvas buckets, or ride on a "bosun's chair," which is a wooden swing that can be tied to a gantline and used to lift a person up into the rigging or down over the side of the ship (like stede during the lighthouse fuckery or lucius when he's supposed to clean barnacles).

for non-maintenance related activities, the only things that really need to be done aloft are loosing and furling the sails.

square sails are kept, when idle, rolled and tied to their yards (furled). fore and aft sails are also furled, which depending on the sail may also mean tying it to a mast, or it may mean bundling it down against a stay or spar.

before a ship gets underway, the sails therefore need to be loosed (untied). a captain might not order all sails to be loosed at once when first starting out. if there's heavy winds, you might only need a few sails to get the speed you're going for. in light winds, you might need all of them. the order of loosing on a ship with five square sails per mast is typically: lower topsail, upper topsail, t'gallant, royal, course. but this is ultimately up to the captain's discretion. the courses have a lot of power and you might not need or want that much power when the winds are high.

to loose a sail, sailors are ordered to lay aloft, where they range out along the yard of the sail they're loosing. they stand on the footropes and hold onto a metal rail called the "jackstay." on each side of the yard, there are 3-5 "gaskets" holding the sail tied to the yard. these are loosed as sailors lay out along the yard (the knot is called a butterfly and can be pulled out in one easy motion). then each person stops at their gasket and "gasket coils" it, which coils the gasket up nicely so that it sits right at the yard and doesn't flap around the sail. gasket coils can also be undone easily by flipping one part of the coil over and then just letting the rest fall. the sail can then be set from deck.

you might need to "sea stow" a sail if you have to furl them very hastily, for example if a storm is coming. in this case you'd lay aloft, loose a couple of gasket coils, and spiral them widely inboard (towards the mast) and tie them off. the goal is not to look pretty, just to be fast. the sail will be doused from deck, and the hardest part of this is gathering up the sail the rest of the way so that it can be tied down. you lean your hips against the yard, reach over, and gather up chunks of the sail, tucking them under your belly until you have all of it, and then tie your gaskets. it's hard to do because you are not working together as closely or as carefully in a sea stow situation, and also potentially because the conditions are garbage.

sails ideally are stored in a "harbor furl," particularly, as the name implies, in harbor, where you are not likely to quickly need them loose again, and you have the time to put them away nicely. also, ship people judge each other if these don't look nice. this is a much more synchronized manuever. the sail is doused from deck, then sailors lay aloft in the same way as they did for loosing. here, the people with the hardest jobs are the ones up first, who go out to the farthest points of the yard (the "yardarm"). everyone begins to gather up the sail in the same manner as a sea stow, leaning over the yard and tucking folds of the sail under your stomach. the people at the yardarm are also dealing with the blocks and gear at the lower outside corners ("clews") of the sails. their job is more technically complicated and so they control the rhythm of everyone's gathering. once the sail has been folded and furled nicely with the "sun skin" facing out (protecting the rest of the sail from the elements), the person on the weather (side the wind is coming from) yardarm calls, in rhythm, "roll-ing home," or something similar, which prompts everyone to roll the sail up on top of the yard in unison. then each person wraps their gasket around the sail and yard, ties it off, and heads back down. again, that command might vary by period and tradition.

5. what are some things I could throw in my story for drama?

here are just a few:

a line could part! this is actually not uncommon on buntlines, which are one of the lines that help set and douse sails. when one of these parts and there's any amount of wind, the whole ship is going to know about it very fast because the sail, out of control, will start to "flog." this means it flops around in the wind and makes a very ominous sound (like a huge towel being snapped). to fix it, crew needs to lay aloft immediately and sea stow the sail so the bosun or other skilled crewmember can rig a new buntline.

a note about lines parting: manila lines do not have the "snapback" effect that modern synthetic lines do. this means they part more easily, but also more safely. they also get VERY swollen and spongy when it's wet, because they absorb water, and may even start to unlay (where the strands start to untwist themselves). so they can be also very annoying to handle when wet.

you might have to execute a manuever while people are still aloft! this is not uncommon, particularly for people aloft performing routine maintenance, but not ideal in bad conditions, particularly if people are out on the yards. because manuevers involve the yards being pulled back and forth and therefore rotating on the mast, it can be pretty harrowing to ride one through a manuever (or fun, depending on what kind of person you are). there are also pinch points between the yards and the mast that anyone on the mast or shrouds needs to steer clear of so they don't get crushed by a moving yard. "avast!" is a real command used when there needs to be an immediate all-stop due to a safety issue.

you might have to sea stow in really heavy conditions! if you've seen the episode of black sails where flint sails the Walrus directly into a storm, you know how difficult this is. when a sail is full of wind, it's very hard to pull it up by hand, even when doused. dousing only pulls the sail about 3/4s of the way up to the yard, and a doused sail can still catch wind. in truly heavy winds it can be almost impossible to stow.

in high seas, the ship could roll so badly that people on the yardarms get dunked in the ocean! this has also happened on black sails, I think in that same episode. this has never happened to me but I think if it ever did I would just rather fall off in the ocean than get swung back up again, thanks (<-guy who is afraid of heights). this is not a death sentence though, sailors can and have held on enough that they get swung back up and can safely get down. if conditions are bad enough that this happens and you do lose grip and end up in the ocean, it's probably going to be pretty difficult to impossible to get rescued, at least in the 1700s.

someone inexperienced might belay a line that needs to be cast off in order for a manuever to work, or vice versa. this could be an easy fix or it could cause a very dangerous situation. if you lose control of one of the halyards that lifts the yards, for example, that's potentially tons of uncontrolled load that could fall and break any number of things on its way. or if a line is made fast when it needs to be loosed, you could have yards raised crookedly and/or lines breaking as the strain becomes too much.

rope burn! the lines on a ship are often controlling a lot of load and power. if you allow the rope to slip through your hands instead of moving hand-over-hand, or if you just lose control of it, you can get rope burn that can be pretty severe. it's a wound that almost looks like a burn from fire would, especially while healing.

-

rcbertpattinscns reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

rcbertpattinscns reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

helly-ena reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

helly-ena reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

prototomatoes reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

prototomatoes reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

takethisawayfrom-me liked this · 2 weeks ago

takethisawayfrom-me liked this · 2 weeks ago -

newdancingnights liked this · 2 weeks ago

newdancingnights liked this · 2 weeks ago -

ughdontbeboring liked this · 2 weeks ago

ughdontbeboring liked this · 2 weeks ago -

lunacy-child liked this · 2 weeks ago

lunacy-child liked this · 2 weeks ago -

lamourdelabeaute liked this · 2 weeks ago

lamourdelabeaute liked this · 2 weeks ago -

auroryyy liked this · 2 weeks ago

auroryyy liked this · 2 weeks ago -

aloha-from-angel liked this · 2 weeks ago

aloha-from-angel liked this · 2 weeks ago -

apple-bread reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

apple-bread reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

wardamuses reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

wardamuses reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

willowwindss liked this · 2 weeks ago

willowwindss liked this · 2 weeks ago -

broadwaydemigod reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

broadwaydemigod reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sephinas reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

sephinas reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sephinas liked this · 2 weeks ago

sephinas liked this · 2 weeks ago -

deepbluelullaby liked this · 2 weeks ago

deepbluelullaby liked this · 2 weeks ago -

caringloving liked this · 2 weeks ago

caringloving liked this · 2 weeks ago -

yiunhi reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

yiunhi reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

yiunhi liked this · 2 weeks ago

yiunhi liked this · 2 weeks ago -

raingardens liked this · 2 weeks ago

raingardens liked this · 2 weeks ago -

honeygentle liked this · 2 weeks ago

honeygentle liked this · 2 weeks ago -

linguinideminonna reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

linguinideminonna reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

linguinideminonna liked this · 2 weeks ago

linguinideminonna liked this · 2 weeks ago -

angelsprint liked this · 2 weeks ago

angelsprint liked this · 2 weeks ago -

callmeyoursokay liked this · 2 weeks ago

callmeyoursokay liked this · 2 weeks ago -

hobidyllic liked this · 2 weeks ago

hobidyllic liked this · 2 weeks ago -

unlikelytowinbutyes liked this · 2 weeks ago

unlikelytowinbutyes liked this · 2 weeks ago -

munsukum reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

munsukum reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

beanie270 liked this · 2 weeks ago

beanie270 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

neoqueen-serenity2 liked this · 2 weeks ago

neoqueen-serenity2 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

mellowdonutcoffee liked this · 2 weeks ago

mellowdonutcoffee liked this · 2 weeks ago -

malditoblog reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

malditoblog reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

malditoblog liked this · 2 weeks ago

malditoblog liked this · 2 weeks ago -

comradeboop liked this · 2 weeks ago

comradeboop liked this · 2 weeks ago -

strawberryjamapplebutter reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

strawberryjamapplebutter reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

cuntkaesque reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

cuntkaesque reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

kulkaaaa liked this · 2 weeks ago

kulkaaaa liked this · 2 weeks ago -

flowersandfashion liked this · 2 weeks ago

flowersandfashion liked this · 2 weeks ago -

village-wizard liked this · 2 weeks ago

village-wizard liked this · 2 weeks ago -

bea-sthetic liked this · 2 weeks ago

bea-sthetic liked this · 2 weeks ago -

winehumours liked this · 2 weeks ago

winehumours liked this · 2 weeks ago -

vivyttely reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

vivyttely reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

vivyttely liked this · 2 weeks ago

vivyttely liked this · 2 weeks ago -

yesitsanusha reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

yesitsanusha reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

tired-iced-americano liked this · 2 weeks ago

tired-iced-americano liked this · 2 weeks ago -

beneaththemooon liked this · 2 weeks ago

beneaththemooon liked this · 2 weeks ago -

me-fish liked this · 2 weeks ago

me-fish liked this · 2 weeks ago

please follow my main blog @kazoo-world this is just a pile of references for me

53 posts