Abstract And Modern Art Haters Are Sooo Snobby Like Klein Literally Created An Entirely New Pigment And

abstract and modern art haters are sooo snobby like klein literally Created an entirely new pigment and then painted a canvas in a way where the brush strokes wouldn't be visible. the insinuation that people with no skill could reproduce that is so annoying because unless you are skilled at color mixing and painting you definitely couldn’t lmao

More Posts from Lrs35 and Others

How to write a novel

I was talking to a girl at ComicCon, the kind of person who has a million creative projects at the same time. As many people do, she has a story she wants to write, with amazing characters she wants to share with the world, but writing is hard and a first novel can be daunting. Here’s what I told her.

Now, this applies to the people who REALLY want to see their story done. These are the main pillars of the cathedral that is your story. Let’s begin.

1- YOUR GOAL IS TO WRITE A COMPLETE FIRST DRAFT. It will be shit. But it will be complete. You can build on it and rewrite, but the most important thing is to WRITE TILL THE END OF THE STORY.

2- SIT DOWN AND WORK. That’s the difference between writers and the million people who say they have a story that they’ll write someday.

Alright, let’s get technical, and start by the end.

3- Art is about causing your public to have emotions. Decide right now what emotion you want to leave your readers with when they close your book. Is it happy, sad, bittersweet, hopeful? Pick one. (This can be changed later if you rewrite and find some other ending, but we are working on the first draft.)

— Maybe you have a nice gimmick, a cool idea for a story, like idk, ‘What if you cloned yourself and that clone took over your life’. This is interesting, but it’s not a story in itself. A story needs emotions. If you don’t pick the emotions you want your reader to feel, your idea is just a gimmick.

4- Now that you have the final emotion, decide your ending in accordance to said emotion. Are characters dying? Is the bad guy defeated? Is everyone splitting up or leaving together as a found family?

Then we go back to the beginning.

5- You probably have a million characters you all want to write. Pick one to be your protagonist. Yes, just one. Multi-characters stories are harder to write and demand experience and time. We want this novel to exist, and not be stuck in limbo forever. Anyway, people tend to always prefer side characters. Who has heard of someone having a protagonist as a fave?? Your side characters will be loved, no worry.

How to find your protagonist: It’s the person who makes decisions and makes the plot advance. Simple as that. Not to be mistaken for the leader of a group.

6- Now that you have your protagonist, you decide what is normal for them. That is your beginning.

7- And then, you break that normality in some horrible way that will prevent your protagonist to come back to it. That is your inciting incident.

Then we write the middle

8- You google Three-Act-Structure and get one of these babies.

(But Talhí, I hear you say, why should I follow this? It’s been overdone, and my story doesn’t follow this, and I have more to write than this… Well, that’s your choice. I’m not the boss of you. I’m just saying that this is a solid model for western storytelling and it’s been proven to work time and time again. You can create outside of this, but again, the main goal here is to get your novel on paper. This is a solid template.)

9- You probably have a general idea of events you want to happen in the story. Place these scenes where you feel they should go on the structure. Like, a confrontation with the main bad guy goes in climax of act three, and the confrontation with the main henchman goes to climax of act two, etc. Be mindful of the rising action and tension: a cute misadventure in the woods would probably go earlier in the story than a fight to the death.

10- Now, a secret: What separates bad writing from good writing? Bad writing is adding a bunch of events in the middle and have the characters go through them like a checklist of scenes. You can often see this in movies. But good writing links the events. Each and every event that happens has to be a result of your character making a decision. Then, an obstacle happens, and your character makes another decision, that leads to your next event/obstacle.

11- Another secret: A character will gain power, money, weapons and allies through the story. In videogames, this is useful to defeat the bad guy. But storytelling is not videogames. Having a superpowerful hero at the end is boring. What we want is keeping the reader in suspense. So you’ll have to take everything from them. Leave them powerless and alone. And then, break their leg. I mean, not literally, although you can do that too, but have them super disadvantaged. And then they can use the personal growth they got in the adventure to prevail. (What is more interesting: a character fleeing from a facility but with weapons and kickass moves, or a character fleeing the same facility without weapons or shoes and with a broken arm? Who do you root for?)

Other tricks

The rest of the crew: I go with what Pixar does for characters: Main character gets three or more characteristics. That’s your Woody. Second tier character gets two characteristics. That’s your Buzz. Third tier characters get one characteristic, like Rex and Mister Potato Head. Keep control of your character tiers and never give too much time to the lower tiers ones, it doesn’t help your story.

Herd your cats: Characters will want to wander in every direction, and you’ll want to follow them. Keep them in groups, and even though you can follow a side character for a scene or two, focus 80 to 90% of your story on your protagonist.

DND is not a novel: I’m pretty sure your campaign is super fun, but you can’t just put it on paper and call it a novel. It needs a narrative arc and serious editing. You can use a campaign as a base, but it needs to be worked as a novel, because you’re changing mediums, and a novel has different requirements.

That’s pretty much what I can remember for now. This should help you with the bones of your novel, and you can add the meat on that. I hope it helps. But honestly, the best advice I can give you is

SIT DOWN AND DO THE THING.

in what order do you think it’s best to read dostoyevsky’s novels?

hey so this is a question i get asked quite often, so you know what? i made yall a handy chart

book covers for horror books are so boring nowadays. they need to go back to being gothic as fuck

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jun/24/overturning-roe-story-is-women-unfreedom

Some aesthetic playlists for writing

For when you’re in an 80s teen montage

For when you’re in a jazz coffee shop in NYC

For when you’re on a quest to find the fae queen

For when you’re in a teen road-trip scene

For when you’re chilling on a spaceship hopping from planet to planet

For when you’re running along the roofs of renaissance Italy

For when you’re a farmhand taking his lunch break in the meadow

For when you’re a high end classy ass art thief

For when you’re kicking butt with the beauty and sass of a k-pop star

For when you’re attending a coronation ball for the crown prince

For when you’re going on an adventure

For when you and your best friends are trying to figure out life together

let me know if you want me to add more!!!

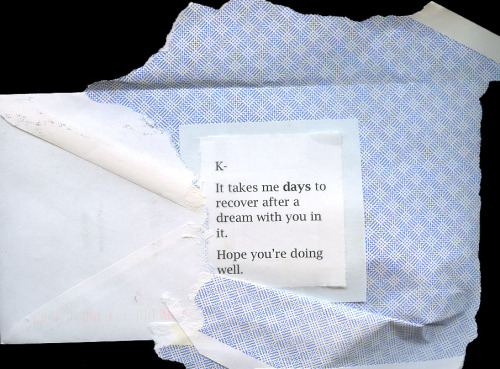

happy valentine's day, also known as international “alex turner's love letter to alexa chung” day.

Any advice on back and forth dialogue? Like properly portraying an argument? I think all the spaces will get bothersome to the reader...

(Since arguments are the hardest type of back and forth dialogue to master, and other dialogue follows the same structure but in a more flexible manner, I’ll focus on arguments specifically…)

Writing an argument.

Everyone’s process for this is a little bit different, but here’s a look at mine, which has helped me reach the best end result (after many failed argument scenes in the past):

1. Dialogue. I like to write this as a script of sorts first, playing the scene in my head and only writing down the words and some vague comments regarding what the characters might be experiencing or doing. I leave breaks in the dialogue where the characters naturally pause from build ups of emotion, and add in all the em-dashes and ellipsis my heart desires (despite knowing a lot of them won’t make it through the reread, much less the final draft.)

2. Action. Not only does having your characters do things while they argue make the whole scene feel more realistic and plant it within the setting, but it also provides a great way for your characters to express things they don’t have the words to say. These “actions” can be facial expressions and body language, movement, or interaction with the objects in the setting, such as gripping a steering wheel too tightly or slamming a cupboard or tensely loading a gun.

3. Emotion. I save this for last because I find emotion very hard to write into narratives, but no matter when you write it or how you feel about it, feeling the pov character’s internal emotions is integral to the reader’s own emotional connection to the argument. Remember though, emotions should be shown and not told. Instead of saying the character is angry, describe what that anger is doing to them physically (how it makes them feel), and what desires it puts in them (how it makes them think.)

Other equally (if not more) important factors:

- Build tension slowly. Arguments will never be believable if the characters go from being calm and conversational to furious and biting in a single paragraph. The reader must feel the character’s anger build as their self-control dwindles, must hear the slight tension in their voice and the sharpness of their words as the scene leads up to the full blown argument.

- Vary sentence length. Arguments in which characters shoot single short sentences back and forth often feel just as stiff and unnatural as arguments where characters monologue their feelings for full paragraphs. If a character does need to say a lot of things in one go, break it up with short, emotional reactions from the other characters to keep the reader from losing the tension of the scene. Likewise, if characters don’t have bulk to their words, try including a few heavy segments of internal emotional turmoil from the pov character to make the argument hit harder instead of flying by without impact.

- Where did this argument start? Most arguments don’t really start the moment the words begin flying, but rather hours, days, weeks, even years before. If you as the author can’t pinpoint where the character’s emotions originated and what their primary target or release point is, then it’s unlikely the reader will accept that they exist in the first place.

- Characters want things, always. Sometimes arguments center around characters who vocally want opposing things, but often there are goals the characters hide or perhaps even from themselves. Think about what goals are influencing the characters in the argument while you’re writing it in order to make sure everything is consistent and focused.

Keep in mind that you don’t have to do all these things the very first draft. My arguments consistently have little emotion and even less build up until the second or third draft. As long as you return to these things as you continue to edit, the final result should feel like a fully fleshed out and emotional argument.

For more writing tips from Bryn, view the archive catalog or the complete tag!

thinking about that one quote from the simpsons about how much homer misses marge

-

geeko-sapiens reblogged this · 1 month ago

geeko-sapiens reblogged this · 1 month ago -

belosers reblogged this · 1 month ago

belosers reblogged this · 1 month ago -

novoki liked this · 1 month ago

novoki liked this · 1 month ago -

firepuddles liked this · 1 month ago

firepuddles liked this · 1 month ago -

moved-accounts-thanks liked this · 1 month ago

moved-accounts-thanks liked this · 1 month ago -

huckleberryhobitti reblogged this · 1 month ago

huckleberryhobitti reblogged this · 1 month ago -

synod liked this · 1 month ago

synod liked this · 1 month ago -

cobaltbluejayy liked this · 1 month ago

cobaltbluejayy liked this · 1 month ago -

zero3finity liked this · 1 month ago

zero3finity liked this · 1 month ago -

zzzaefer liked this · 1 month ago

zzzaefer liked this · 1 month ago -

metroid963 liked this · 1 month ago

metroid963 liked this · 1 month ago -

s-dot-o liked this · 1 month ago

s-dot-o liked this · 1 month ago -

ombrekaleidoscope liked this · 1 month ago

ombrekaleidoscope liked this · 1 month ago -

theoriginalkea reblogged this · 1 month ago

theoriginalkea reblogged this · 1 month ago -

eerie-dearie-arts liked this · 1 month ago

eerie-dearie-arts liked this · 1 month ago -

gi-ie-ru reblogged this · 1 month ago

gi-ie-ru reblogged this · 1 month ago -

spawn-sun liked this · 1 month ago

spawn-sun liked this · 1 month ago -

maudie-beans liked this · 1 month ago

maudie-beans liked this · 1 month ago -

nemossubmarine liked this · 1 month ago

nemossubmarine liked this · 1 month ago -

skelebeee reblogged this · 1 month ago

skelebeee reblogged this · 1 month ago -

teacorgi liked this · 1 month ago

teacorgi liked this · 1 month ago -

valkyrie-girl reblogged this · 1 month ago

valkyrie-girl reblogged this · 1 month ago -

cleargobrrrrrrrrr liked this · 1 month ago

cleargobrrrrrrrrr liked this · 1 month ago -

gabrielleincursive reblogged this · 1 month ago

gabrielleincursive reblogged this · 1 month ago -

lavendermoon48 reblogged this · 1 month ago

lavendermoon48 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

lavendermoon48 liked this · 1 month ago

lavendermoon48 liked this · 1 month ago -

gef-the-talking-mongoose reblogged this · 1 month ago

gef-the-talking-mongoose reblogged this · 1 month ago -

gef-the-talking-mongoose liked this · 1 month ago

gef-the-talking-mongoose liked this · 1 month ago -

flame-cat liked this · 1 month ago

flame-cat liked this · 1 month ago -

littleinkreblogs reblogged this · 1 month ago

littleinkreblogs reblogged this · 1 month ago -

0ct0puppy reblogged this · 1 month ago

0ct0puppy reblogged this · 1 month ago -

0ct0puppy liked this · 1 month ago

0ct0puppy liked this · 1 month ago -

writer-fennec liked this · 1 month ago

writer-fennec liked this · 1 month ago -

derflauschigstefuchs reblogged this · 1 month ago

derflauschigstefuchs reblogged this · 1 month ago -

solitarywoman liked this · 1 month ago

solitarywoman liked this · 1 month ago -

valkyrie-girl liked this · 1 month ago

valkyrie-girl liked this · 1 month ago -

tere112 liked this · 1 month ago

tere112 liked this · 1 month ago -

hiraethoharth liked this · 1 month ago

hiraethoharth liked this · 1 month ago -

gautiergloom liked this · 1 month ago

gautiergloom liked this · 1 month ago -

starthistlemoon reblogged this · 1 month ago

starthistlemoon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

capnbulbasaurr liked this · 1 month ago

capnbulbasaurr liked this · 1 month ago -

unironicallyresurrected reblogged this · 1 month ago

unironicallyresurrected reblogged this · 1 month ago -

queen-of-lyres liked this · 1 month ago

queen-of-lyres liked this · 1 month ago -

autisticsupervillain reblogged this · 1 month ago

autisticsupervillain reblogged this · 1 month ago -

souryellows liked this · 1 month ago

souryellows liked this · 1 month ago -

starspangledpumpkin reblogged this · 1 month ago

starspangledpumpkin reblogged this · 1 month ago -

melophobia2013 reblogged this · 1 month ago

melophobia2013 reblogged this · 1 month ago -

embroiderbees liked this · 1 month ago

embroiderbees liked this · 1 month ago -

anathecatlady reblogged this · 1 month ago

anathecatlady reblogged this · 1 month ago